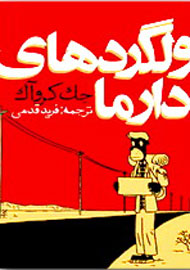

Oh, hey, that’s an ad for my book on Salon!

Oh, hey, that’s an ad for my book on Salon!

“What makes a book a classic,” wonders Laura Miller in Salon.

Wouldn’t you know it, Jack Kerouac’s On the Road gets a mention, amongst works by Seamus Heaney, Kurt Vonnegut, David Foster Wallace, Daphne du Maurier, P.G. Wodehouse, Toni Morrison, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Alexandre Dumas. Miller writes:

And what about “On the Road” which to the same reader might seem like an incontestable classic at age 17 and sadly or sentimentally jejune at 45?

Her question in regard to Kerouac’s most famous novel raises some questions of its own:

- Does our definition of “classic” change with our age?

- Is On the Road definitively insignificant after age 45?

- Does content matter more than literary style even for the classics?

But let’s go back to the discussion at hand for a moment to build some context. In her article, Miller points to an interesting discussion on Goodreads:

A fascinating Goodreads discussion on this topic shows participants tossing out all the most common defining characteristics of a classic book. It has stood the test of time. It is filled with eternal verities. It captures the essence and flavor of its own age and had a significant effect on that age. It has something important to say. It achieves some form of aesthetic near-perfection. It is “challenging” or innovative in some respect. Scholars and other experts endorse it and study it. It has been included in prestigious series, like the Modern Library, Penguin Classics or the Library of America, and appears on lists of great books. And last but not least, some people define a classic by highly personal criteria.

She also references an essay by an Italian journalist, translated by Patrick Creagh in 1986:

Perhaps the most eloquent consideration of this question is Italo Calvino’s essay, “Why Read the Classics?,” in which he defines a classic as “a book that has never finished saying what it has to say,” among a list of other qualities.

So does On the Road fit these contrived attributes of a classic?

- Has On the Road stood the test of time?

- Does On the Road hold eternal truths?

- Does On the Road capture its era, the 1940s and ‘50s?

- Did On the Road have a significant effect on the 1950s?

- Does On the Road have something important to say?

- Does On the Road achieve some form of aesthetic near-perfection? Side question: Is aesthetic near-perfection something we can define or is it subjective??

- Is On the Road challenging? Side question: Does challenging mean from a reading-level standpoint? From a philosophical standpoint?

- Is On the Road innovative?

- Has On the Road been included in a prestigious literary series?

- Has On the Road appeared on a list of great books?

- Does On the Road fit your own personal criteria of classic?

- Has On the Road ever finished saying what it’s had to say?

Okay, many of these can be objectively answered as “yes.” One can point to numerous sources that show that Kerouac’s road novel rocked the era in which it was published and continues to be discussed by scholars and pop culture alike today. A few seem debatable, but I would argue that anyone knowledgeable of literary history and criticism would agree—from a literary standpoint—that On the Road is innovative (read Burning Furiously Beautiful for in depth analysis of Kerouac’s literary style) and therefore challenging in both style and content. It also speaks to eternal verities (notably the search for it, for meaning) and therefore has something important to say and continues saying it afresh to new readers. The two questions that remain because they are the most subjective are:

- Does On the Road achieve some form of aesthetic near-perfection?

- Does On the Road fit your own personal criteria of classic?

I’d love to hear your thoughts on wrestling with these questions. Is On the Road a classic?

One thing that struck me—hard!—when I was reading Miller’s thought-provoking article is that I immediately agreed that David Foster Wallace’s work is a classic, but was put off by J. R. R. Tolkien being included. While this shows my own personal bias, if pressed I would concede that Lord of the Rings is “a classic” but not “a Classic.” It is, after all, fantasy—genre fiction. And in my mind, as in many other people’s mind, there is a distinction, a dividing line in literature. For some reason, I can concur that magical realism can fall under the category of classic but have a more difficult time with fantasy. Yet, if I hold Lord of the Rings up to the same questions as On the Road, I’m hard-pressed to deny it’s a classic. So what is a classic? What standards should we agree to when defining a work as classic? Are there classics and Classics?

And why do Lord of the Rings nerds get a free pass for liking Tolkien well into their adult years while society derides Kerouac as a novel just for teenagers??

Tags: Beat Generation, Daphne du Maurier, David Foster Wallace, genre, Goodreads, J. R. R. Tolkien, Jack Kerouac, Kurt Vonnegut, Laura Miller, On the Road, P. G. Wodehouse, Salon, Seamus Heaney, social media, Toni Morrison