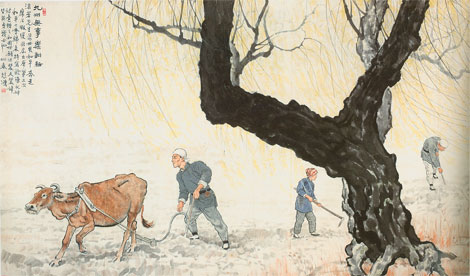

Burnside published my art post “A Time to Plant and a Time to Uproot” today.

It only occurred to me as I was posting this clip how interesting it is that Xu Beihong’s painting is from 1951. Doesn’t the seemingly traditional shuimohua painting seem much older? Xu is actually known for his Western sensibilities and is considered a forerunner in modern Chinese art.

Xu studied calligraphy with his father before attending the famous École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts — you know, that Parisian school where Degas, Matisse, Monet, and Renoir studied at. In 1917, Xu Beihong went to Japan to study art. During World War II, he sold his paintings in exhibitions throughout Asia, giving the proceeds to the Chinese whose lives had been upturned because of the war. As a teacher and artist, Xu’s policies greatly influenced the way both colleges and the government respond to art in Communist China. He died in 1953.

Meanwhile, over in Oregon at Reed College in the early 1950s, Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen (who served Stateside during World War II), and Lew Welch–who are associated with the Beat Generation–were studying with calligrapher Lloyd Reynolds. Snyder and Whalen later spent time in Japan, where they studied zen. The US State Department initially denied Snyder a passport, alleging he was a Communist.

Asian influences can also be seen in the art of the time period, most notably the abstract expressionist art of Franz Kline, Adolph Gottlieb, and Theodoros Stamos. Note this opening paragraph from the Guggenheim’s article “Abstract Art, Calligraphy, and Metaphysics“:

Following World War II New York City became the center of the avant-garde art world. Artists were working in new ways, and some were exploring the energy of the gesture with loose brushwork that reflected the impact of the artist’s bold movements. The calligraphic brushstroke was an approach to abstract painting that focused on the spontaneous gesture of the artist’s hand and was informed by the East Asian art of calligraphy and popular writings on Zen and its principles of direct action.

The article goes on to say:

In Chinese and Japanese calligraphy the brush becomes an extension of the writer’s arm, indeed, his or her entire body. The artist’s stroke not only suggests the movement of the body, but also inner qualities. Abstract as it appears, calligraphy also conveys something about the essence of the individual artist. It is therefore not surprising that 20th-century American Abstract Expressionists who sought to convey emotion through paint were drawn to it.

Because so many soldiers were stationed in the East during World War II, both the West and the East were influenced by each other.

What I personally find fascinating with calligraphy is the collision of art and literature, the visual and the literal, words becoming art, and art becoming words.

Tags: Abstract Expressionist, Adolph Gottlieb, École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, calligraphy, China, Communism, France, Franz Kline, Gary Snyder, Japan, Lew Welsh, Lloyd Reynolds, Oregon, Paris, Philip Whalen, Portland, Reed College, Theodoros Stamos, visual arts, World War II, zen