I had a really fun time putting together an article for Burnside about poets who are also visual artists. From the time I was a little child, I have been drawn to both the literary and visual arts worlds. Even in undergrad these two loves of mine co-mingled, as I majored in English and minored in studio art. My undergrad thesis looked at the relationship between writers and artists in New York in the ’40s and ’50s. It didn’t end there. While obtaining my MFA in creative writing, I took a poetry class on the collaborations of the poets and artists of the New York School. My article touches on some of the poets I’ve studied over the years, with of course a focus on the people commonly associated with the Beat Generation, but I pushed myself to find other examples as well.

Our cannons are so steeped in “dead white males” that it was important to me in stretching my knowledge to seek out poet-artists who did not play into that categorization. I was delighted to discover that Elizabeth Bishop painted. Two years ago it was the hundred-year anniversary of the former Poet Laureate of the United States’ birth, so there were many readings and events to honor her work. Somehow, though, I missed the fact that she was a painter. Maybe it’s because she herself did not take it all that seriously, as I point out in my article. I happen to think they’re delightful, though.

A contemporary poet-painter I am quite interested in researching more about is Babi Badalov. As my article touches on, he mixes languages in his works, a result of having moved a lot between cultures to avoid persecution for his controversial visual poetry. As a writer, language is something I hold dear. My vocabulary is a key to who I am: the words I’ve picked up come from my mother’s midwestern phrasing and my father’s Greek tongue as well as the vernacular of northern New Jersey and the jargon of the institutes of higher learning I attended. I’ve found the preservation of endangered languages so critical because language is about identity. The idea that a poet has no language and has many languages intrigues me. When does Badalov express himself in his native Azerbaijani language and when in Russian? Is his use of English a political act?

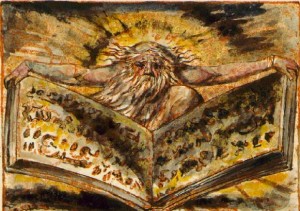

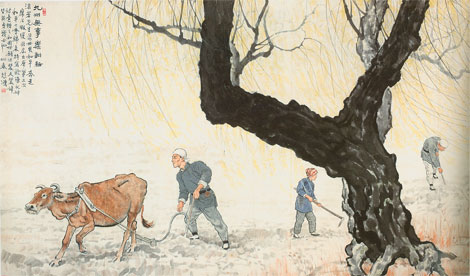

In my exploration of the Beats as visual artists, I could have easily waxed on and on. In fact, I did not go into any detail about Jack Kerouac’s artwork, even though he has been the subject of much of my studies. If this is something you’re interested in, leave a note in the comment section below, and I’ll write something up on this. What I did try to do for the Burnside article, though, was show that the Beats were following a rich tradition that came long before them. I point to William Blake and the Chinese and Japanese calligraphers as forerunners and influencers on the work of Allen Ginsberg and Phillip Whalen, for example.

My article was limited to just a few examples, a small taste of the artwork of poets. I’d love to hear who you think should be added to the list. Maybe I’ll make a part II!