Tim Z. Hernandez photo courtesy of the University of Arizona Press

Tim Z. Hernandez photo courtesy of the University of Arizona Press

I’ve often thought that poets make the best prose writers, and I was reminded of this once again as I read award-winning poet Tim Z. Hernandez’s novel Mañana Means Heaven. The story is about Bea Franco, the real-life woman who inspired Jack Kerouac to write one of the most poignant passages in On the Road—the story of “the Mexican girl,” Terry. Mañana Means Heaven is by no means a work of fan fiction. It is beautifully crafted and painstakingly researched, and stands on its own. Even as I got caught swept up in the story, I kept wondering how Hernandez did it—how was he able to write such a captivating story about a real person, one he’d met and interviewed, one whose children he’d met, who for so long seemed mythical herself yet was perhaps overshadowed by Beat mythmaking?

When the University of Arizona Press asked me if I’d be interested in participating in a blog hop with Tim Hernandez, I jumped on the opportunity. Special thanks to the University of Arizona Press for arranging this interview and for being great to work with. And, of course, a big thanks to Tim for so thoughtfully answering all my questions.

* * *

How did you first come across Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and how old were you?

I first read it when I was around 17. I believe a friend of mine from Sweden, Jonas Berglund, turned me onto it. He was the poet back then, while I was mostly into painting. He was trying to get me to go backpacking with him in Europe, and he kept telling me how cool it would be. He told me I should read “On the Road,” so I did. That summer I split with him to Europe.

What did you think of it at the time and how has your perspective on the novel changed over time?

I’ve read OTR three times now. At age 17, and then in my early twenties, and then later at around 30. At age 17 I identified with the desire to break free, to adventure and take risks, to get away from the place I called home. In my early twenties I began questioning whether or not these guys, Kerouac and his crew (The Beats), were just completely insane. Also, the idea of a threshold appeared. I related more with the underlying question Sal Paradise was seeking to answer, that is, do I continue on this path of wild abandon, this path as perpetual seeker of truths, by whatever means, OR, do I fall in line with the rest of the world and live a “normal” life clocking in day to day and having a family? It was a matter of maturation. Not that I decided to let go of that desire “to seek” but just that I would go about it differently, in my own way. And then by age thirty, I was reading the book less for its subject and more for the writing itself, the technique and process, and also the idea of lineage. This is what sparked the initial seed for Mañana Means Heaven.

In the introduction to Manana Means Heaven, you say that you became interested in the story of “the Mexican girl” Terry/Bea Franco because it was the part of Kerouac’s novel that you could relate to. I understand that your parents were migrant workers near where Bea’s family worked as migrant workers. I know you also worked for the California Council for the Humanities interviewing immigrants about their lives and struggles. Were your parents immigrants? Can you talk a little about your relationship to and interest in the migrant worker experience and how it relates to your writing?

Yes, all of this was very influential to my wanting to write about Bea Franco. My work with CCH, and even the Colorado Humanities today, has been very instrumental in the research and process for the making of this book. It’s the experience of working for them that has emboldened me to walk up porches and knock on the front doors of total strangers, for the sake of stories. Not to mention, having these two entities as a resource throughout my research has been invaluable. As for the other part of your question, my parents were migrant farmworkers, but they were born in Los Angeles and Texas, so they weren’t immigrants. I’m the third generation in my family to be born here in the United States, and I think this is also why I related to Bea so much once I finally met her. My first question to her was, “What do you think about being called the Mexican Girl?” She laughed and replied, “I’m not from Mexico, I was born in L.A..” So she was very conscious of her own identity in this way too. She was not an immigrant by any means, and I believe that it’s possible this assumption about her is what kept Kerouac biographers from finding her, or even looking. In any case, having come from the same background as Bea Franco, the farmworker experience, living among the labor camps of the San Joaquin Valley, this was all part of my growing up. My parents and grandparents used to travel all over picking crops, grapes, hoeing sugar beets, so I knew the people from this place very well. When Sal Paradise entered the San Joaquin Valley in “On the Road” I felt he was now entering my world, a distinct place that is in every fiber of who I am, and I knew I could write about this with some authority.

Similar to your experience with Bea Franco, part of what continues to draw me to Kerouac is his ethnic experience and how he writes about feeling a duality within him. I was born here in New York City, but my father is an immigrant. He moved here from Greece when he was in his thirties, and he felt embarrassed because sometimes people couldn’t understand him because of his accent. Kerouac’s parents were immigrants from Quebec, and although he spoke English as a child he really didn’t feel comfortable with the language until he was a teenager. I think our immigrant experience was much different, though, because of our skin color. Kerouac is seen as a quintessential American novelist while Bea got pegged as “the Mexican girl” even though they were both born here in the States. Was Kerouac’s portrayal of the immigrant experience something you were interested in or were you mainly interested in telling Bea’s story?

Yes, all valid points here. Bea too was in that strange purgatory of “immigrant born in the U.S.,” and she too was very light skinned with green eyes, and because of it was sort of an insider-outsider, similar to Kerouac’s and your own situation. In some of our conversations she talked about how she was treated differently, sometimes cruelly, while growing up because of her complexion. In many ways, hers was a real “Chicana” experience, before the term was popular. She was balancing between two cultures at once, was educated in Los Angeles public schools, spoke fluent English and Spanish. She loved both the Mexican classic songs, and the big bands of her time. In 2010 she still had stacks of records by Tommy Dorsey and Glenn Miller, folks like that. When I first met her she had a portrait of Ronald Reagan in her dining room. It took my aback for a moment, until I asked her about it. I was afraid she’d say something like, “He was our greatest President.” But instead, she said, “He was a great actor and I loved his movies,” and then she chuckled. Bea loved being American, and even though her father was from Mexico she clearly identified with aspects from both sides of the border. In regards to the last part of your question, yes, I was mostly after Bea’s story, about who she was/ is. As a fan of Kerouac’s writing, in the beginning it was tough for me to distance the two, but it was necessary to do so. If I was to write about Bea’s life, to fill in that “missing link” about who “The Mexican Girl” was, I had to start from scratch. That is, I had to, in some ways, reject what other biographers had written about her, and even reject what Kerouac himself had written about her, and go straight to the source—Bea and her family—and start there. So then the question of what she remembered of her time with Jack was no longer significant. Instead I would ask her, Tell me who you are? Where were you born? Who did you love? Approaching it this way would allow readers to enter the book on her terms, not based on anything else written about her previously. This is what I was after.

The Beats have often been criticized for the way they treated and portrayed women. In fact, I have been criticized in the media for being a woman who likes Beat writing. You’ve given voice to one of the most influential women connected to the Beats. The story of “The Mexican Girl” was the first part of On the Road Kerouac got published in a lit magazine. Some might argue that Kerouac used her for her body or for gaining experience for his book. Your depiction of their relationship was quite tender and sympathetic toward both of them. It reads like a beautiful love story. What was your thought process in writing about Bea striving to make a change in her life and cheating on her husband, and Jack leaving and never reconnecting with her?

Yes, my initial idea, as I started to envision the book, was that I’d somehow have the opportunity to “even the score.” That I would make Jack out to be this womanizer only after his own “kicks” or “experiences.” Of course, this was still before I had ever met Bea. Too, I think in order to write a good story, an honest or authentic story, at least in this case, one has to suspend those kind of judgments about their own characters. This occurred to me after I had met Bea and began speaking with her. She never viewed herself as the “damsel in distress,” and in fact, was a woman who took responsibility for her own decisions, in her early years and even now, yet was also very much a romantic. After speaking with her I quickly saw that she was not the naive “Mexican Girl” that Kerouac made “Terry” out to be in “On the Road.” Nothing in our conversations told me that for Bea, at least in her own mind and heart, ever doubted their relationship was a real possibility. Of course, she was aware that this could also mean a new start for her and her children. And this is the sense I get too from reading her love letters to him. In the end, the relationship had to feel like a very real possibility, for her mostly, but for Kerouac too. Because if he didn’t believe in it, then going by what I know about her, she would not have wasted her time.

You tracked down the real Bea Franco and got to know her. How did she feel about being a character in Kerouac’s novel and how open was she when answering questions for your book?

When I located her in September 2010, she nor her children had any clue about the legacy of “The Mexican Girl.” She was just about to turn 90 years old, and when I did tell her, I said something to the effect of, “Did you know you are a famous character in a famous American novel?” Her children, Albert and Patricia, laughed out loud. Bea just sort of nodded and said, “Oh really. I didn’t do nothing so special.” The next thing I did was take out a list of over 20 Kerouac biographies that mention her name. She just shrugged, like it was no big deal. Her son though, Albert Franco, who Kerouac dubbed “Little Johnny” in On the Road, he opened up his laptop and started typing stuff into the search engine. There he was now at age 70, blown away by it all. I can’t describe the feeling of it, but the word “surreal” comes to mind. I just sort of sat there praying they wouldn’t kick me out of the house. A couple of visits later, while interviewing Bea, Albert asked me, “After all these years…how can so many people mention my mother’s name in their books and never tell us about it?” I didn’t have an answer for them. But I knew right then that I had already done a couple of interviews and still had not formally asked their permission. I felt, symbolically at least, that this was necessary. So I asked her point blank, “Bea, can I write the book about your life?” She said, “Sure.” I replied to her, “What would you like the world to know about you?” She answered, “Oh, I guess that I tried hard to be a good person.” Albert was sitting with us too. At the time he looked reluctant with the idea of yet another book. I told him, “People will continue to learn about your mother from all these books, or I can write the only book with her input, her own words, from her perspective, and after that everyone will no longer guess at who she is.” I think it was after he did his research on me and saw that I was a kid from Fresno whose parents were also migrant farmworkers, did he finally begin to trust me. Of course, Albert and I are now great friends.

How did her children react? You uncovered Bea’s affair and described her and Jack’s relationship in pretty sensual terms. Did you feel any awkwardness writing about any of this or any responsibility toward her and her family for how you portrayed the events?

Patricia and Albert are both very proud of the book. As are the rest of their family and friends, many of who are the children or grandchildren of some of the background characters in my book. As for the “sensual” aspect, this is probably where I had the toughest time writing the book. Which seems weird coming from me, since both of my first two books have been called “raw,” “graphic,” “sexual,” in past reviews. But here I was dealing with someone else’s life, not purely my own imagination. My first attempts with the love-making scenes were horrible. A good friend who was a first reader told me, “You’re writing as if Bea herself is standing over your shoulder.” And this was true. I was worried about losing the trust of her and her children. I didn’t want it to come across as distasteful. But still, in order for anyone to be convinced of this romance, an affair where two adults holed up in a hotel room for several days, then the range of intimacy had to be present—everything from long talks in the wee hours of the night, to the ebb and flow of emotions, sex, regret, risk, liberation, all at once. I’ve long considered myself to be the kind of writer who doesn’t shy away from “the real,” and in fact, this is what I returned to as the book was being written.

Manana Means Heaven is categorized as a work of fiction. How much of it is true? In literature, where do you think the lines are drawn between fiction and creative nonfiction?

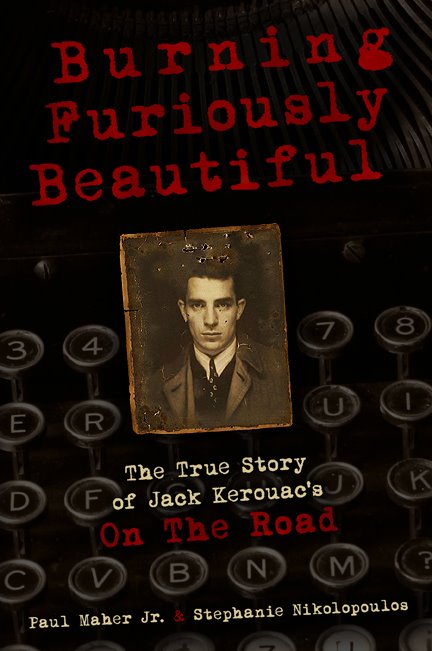

This is the kind of question that would require many pages to even scratch the surface, so I’ll try and give you the brief version. “Fiction” and “Creative Non-Fiction” are genres, and I treat them as such. Neither are qualified substitutes for “the actual.” Isn’t this part of what Kerouac’s own legacy is built on? The idea of writing it as he lived it? If I had to put it into a percentage I would say about 75% of Manana Means Heaven is “true” from Bea’s perspective. The other 25% is authored by me, but also rooted in truth, about the life of farmworkers in the 1940’s, about the history of that part of California and the people who worked the land. Like I told Bea herself, even though it’s called “fiction” it’s still closer to the truth about who you are than anything else out there. Which is odd when considering that most of what is out there can be found in the “Non-fiction” books shelves. Reason being is that biographers have only counted on Kerouac’s version of events. One of the first biographers I contacted when my research began was Paul Maher Jr. This was because his book, “Jack Kerouac’s American Journey” had the most unique pieces of information about Bea than any other book out there at the time. I wondered how he knew certain things, so I asked him. Turns out he had read Bea’s letters to Kerouac, which were housed in Kerouac’s archives at the New York Public Library. So Maher had dug a little deeper than most in regards to Bea. And now only recently, Joyce Johnson’s new book “The Voice is All” has echoed some of what Maher had discovered. I imagine now that my book is out we’ll start to see more accurate information about Bea Franco, which is also a big part of why I wrote this book.

You’re also an award-winning poet. I think poets often make the best writers. Can you talk a bit about how you approached this novel as a poet or how the writing process differed?

Yes, ultimately, I feel at home with poetry. For me, prose is like going to work, slinging a hammer from 6am–5pm. Poetry is like the ice cold beer you crack open when the day is done. Poetry was my focus throughout my undergrad and graduate degrees. But I do love telling stories too. Why can’t both happen? In writing I don’t begin by saying “I’m going to write a poem today.” Or, “I’m going to make this a story.” I write and allow the muse to tell me what it is. Even then I’m skeptical, or open about it. I keep writing until I get to a point where I go, okay, now I have to make a decision here. In the end, my main goal is tell a damn good story. It so happens that for me a good story is one that works on multiple levels. Not merely subject, but on the line level. For me a good story also has language that sings, that isn’t afraid to dig deep in the crates, use fresh turns of phrase, make rhythm, use imagery that evokes emotion.

Can you talk a little about the literary device you used in opening and closing the book in the same way?

Yes, there are two ends to the book, Bea’s story, and then my search for Bea. The idea of starting the book at the second ending emerged somewhat organically. I had to figure out how to let the reader know that this book is rooted in my interviews with Bea, and I had to address the one thing that I knew would be on the minds of Kerouac fans, that is, what did she remember of her time with Kerouac. And then there was one big wrench in the machine that I also had to figure out how to get around. By starting from the very end of what is considered the “non-fiction” portion I was able to set these three things up so that when the reader finally enters the “fictional” portion of Bea’s story, they have suspended their idea of “fiction.” The book went through something like twelve drafts before I could figure this part out. There was a lot of shuffling chapters around and reconfiguring the whole thing…in fact, there were times when I thought to myself, who am I kidding? It’ll never work. But I finally found a combination that did work.

* * *

Tim and I will be continuing this conversation this Thursday night at La Casa Azul.

* * *

Meanwhile, join Tim Z. Hernandez on the rest of his blog-hop!

Tim Z. Hernandez Blog Tour:

Tuesday, September 17 | The Daily Beat http://thedailybeatblog.blogspot.com/

Wednesday, September 18 | La Bloga http://labloga.blogspot.com/

Thursday, September 19 | The Big Idea http://www.jasonfmcdaniel.com/

Friday, September 20 | The Dan O’Brien Project http://thedanobrienproject.blogspot.com/

Saturday, September 21 | Impressions of a Reader http://www.impressionsofareader.com/

Tags: Bea Franco, feminism, immigrant, interview, Jack Kerouac, Joyce Johnson, La Casa Azul, Mexico, Next Big Thing Blog Hop., On the Road, Paul Maher Jr., the immigrant experience, Tim Z. Hernandez, University of Arizona Press

via Warby Parker

via Warby Parker